Things thought too long can no longer be thought

For beauty dies of beauty, worth of worth.1

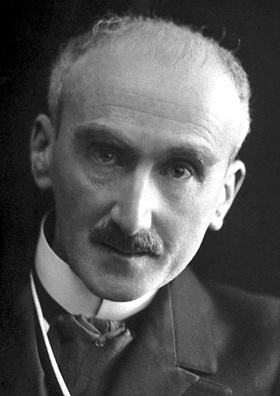

These lines of William Butler Yeats were published in 1939, the last year of his life in which decades of turmoil in his native Ireland were about to be succeeded by World War II. In our time we are aware that a great shift is underway with liberal democracy being dismantled by an authoritarian U.S. regime while climate change undermines the conditions for continued life on earth. Major cultural change is needed to restore our natural and human systems to health – change that we know cannot be return to the failed models of the modern age that have caused environmental devastation, genocide and extreme wealth inequality. Thankfully we are seeing a profusion of alternative designs, frameworks and worldviews being put forward aimed chiefly at achieving environmental and social sustainability as well as robust democracy. As actual conditions become worse, such visions seem increasingly utopian and thus impossible insofar as they lack reliable pathways to actualization. The majority of people need to act, but they remain largely unenlightened as to what they can and should do. A new understanding of the world and their life in it can guide them, and this is what this essay offers, drawing from our cultural heritage, especially the thought of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century French philosopher Henri Bergson.

His work contains several brilliant and extremely timely insights on the nature of time, consciousness and the unconscious, materiality and immateriality, life and non-life. He supports his metaphysical ideas with extensive scientific evidence taken from the physical, biological and social sciences of his time that to a large degree are upheld by our common everyday experience. As his thinking is traced from Matter and Memory through Creative Evolution and The Two Sources of Morality and Religion it is found to lead into Aristotle’s essentialist ontology, adding ecological and true temporal dimensions to that ancient Greek philosophy. The expanded Aristotelianism that results is not only more consistent with common sense but particularly fitting to guide moral action today.

I therefore summarize Bergson’s philosophy, then point out where it fails to accurately represent common experience and Aristotle’s system succeeds. Synthesizing the two I proceed to lay out a new vision of the world and direction for human action. Following the tradition of commentators approaching the French philosopher’s thought from diverse angles, I have chosen to center my exposition on Becoming, which I write with a capital B.

The core truth of Bergson’s work is that the present is and the past is not. He therefore describes the world as continually coming into being anew and passing away into the past in every present moment which is not instantaneous but rather temporally extended in what he calls “duration.” This position is radically opposed to the basic scientific conception of time which is that it is a series of extensionless instants that are represented on time/distance graphs. It is also opposed to the ancient Greek view of time as an eternal present. For Bergson Becoming is the universe which is not only temporally extended but also spatially “extensive.” Becoming is therefore substantive and “possesses something akin to consciousness, something akin to sensation.”2

Becoming is immediately known in the act that he calls “intuition” wherein we relax our attention to the distinct images in our experience, becoming conscious of the ever-renewed present and its passage away into the past.3 In intuition the apparent distinction between subject and object dissolves; images become indistinct and variable, and we are aware of them passing into memories through which the past is prolonged into the present. Within this spatially extensive and temporally extended intuition multiple indistinct and variable qualities are also experienced as being interpenetrated by memories. This phenomenon is evident in normal experience in which we look at some object, observe the passage of time and then realize that our image of the object has become to some degree a memory and no longer just an immediate present perception. Usually we are not conscious of subtle changes in things’ appearances, only noticing change at a certain threshold, and this is a matter of daily experience as, for example, natural light continually changes the colors of objects that we see as remaining the same over intervals.

For Bergson the universal Becoming contains extensive and qualitatively different but not distinct qualities that constantly change in a kaleidoscopic manner as they continually come into being and pass away into the past. He conceives material objects after Faraday’s definition of the atom as “a center of force.”4 Their materiality consists in the continual repetition of their pasts within Becoming, with this repetition constituting the determinism of their action.5 He calls the human body a “center of action”6 that occupies a “zone of indetermination.”7 Material things including the body have diverse “rhythms” of duration8 which are the frequencies with which they repeat their pasts.

Matter and Memory explains experience in these terms first descending to an elementary cosmic level. Here we conceive entities like bodies or configurations of energy in constant flux with each one conditioning and being conditioned by all the others.9 While they do interact with actual contact between them, they also virtually act as, for example, by exerting gravitational force upon each other. Bergson asserts that that all these entities produce “images” which are reflections back to them of their virtual action upon others.10 In the case of gravity, one entity’s gravitational force has a distinct effect upon another entity which then figures in the latter’s effect upon the former. This is the reflection which for Bergson defines the image. It is the intersection, so to speak, of the two entities’ virtual action upon each other.

He opens Matter and Memory with the statement that the body is surrounded by images and is itself an image.11 While he goes on to considerably elaborate this claim, it brings to our attention a self-evident fact of experience that remains essential to his whole philosophy which is that experience isn’t in the body, but rather the body is in experience. As intuition reveals and energy physics affirms, the body isn’t a discrete thing but is indefinitely extended in the world, ultimately influencing every part. Further, because consciousness is inherent in the substance of the world, such influence accounts for the production of conscious perceptions within that substance outside the boundaries of the body. According to Bergson we are not immediately aware of the images surrounding us because they are dispersed and discontinuous. Consolidating them into the images of our familiar experience is the work of our attention and memory.

Virtual action for the body concerns the fulfillment of its organic needs12 which involve moving among and affecting external objects. So the images it perceives are reflections of such virtual action that especially distinguishes objects as separate and determines their spatial qualities13 including their distance away from the body, indicating where it might touch and grasp them as well as how far it must move to come into contact with them. Virtual action may immediately become actual as with the amoeba which, upon touching some object reflexively performs some action upon it.14 Perceiving images of objects at some distance from the body creates a delay in the response which enables the subject to choose whether or not to carry it out and also to review alternatives.15

The body therefore contains an elaborate sensori-motor apparatus to translate perceptions into motions. Its materiality consists in the repetition of its past or habitual functions which Bergson calls “bodily memory.”16 Virtual actions are the projection of bodily memories into the body’s environment that are determined by its present attitude.17 As they are reflected by surrounding objects they form images that initiate motions in the senses that continue through the nervous system and may finally issue in some muscular action. He calls such immediate perceptions “pure perceptions”18 that occur in the present moment which has minimal duration.

Images of pure perception unite the body with its object and provide a momentary intuition of its particular quality.19 Discussing pure perceptions Bergson descends to the micro scale and has them displaying a high level of flux, coming into being and passing away moment by moment. He offers the example of color as it is scientifically understood as electromagnetic radiation, identifying the periods of its duration with its frequency, from which he infers that the temporal continuity of our normal experience does not come from pure perception. Instead, a continuous series of memory images comes forth to overlay and merge with pure perceptions, contracting their high frequency or rapid rhythm of duration into the body’s much lower frequency or slower rhythm, producing what he calls continuous intuitions of apparently solid and enduring objects.20

Bergson distinguishes bodily memory from image memory. In the course of its Becoming the body continuously accumulates its past, and this is a matter of common knowledge. Everything that happens in and to the body is preserved by it for the remainder of its life, taking the form of marks such as scars and habits or the ability to reproduce past actions. We consciously memorize lessons in order to repeat them at a later time, but singular actions are also preserved, initiating or compounding habits that are built over time from similar but not identical experiences. Learning to drive a car exemplifies this process.

Image memory is the preservation of every conscious perception that one has ever had, and it too continually accumulates not in the body but rather in what Bergson calls “the past” which in Matter and Memory he initially describes as being of a spiritual nature.21 Image memories from the past re-enter the present to overlay pure perceptions that are momentary and indefinitely spatially extended, converting them to temporally continuous present conscious images with definite spatial extension.22 Through this process the flux of Becoming is solidified into the stable images of our normal experience.

Phenomena are frozen in this manner in order to permit the body to survey their multiplicity and choose which of the virtual actions embodied in them that it wishes to actualize.23 The past in which memory images dwell contains what Bergson calls “planes of consciousness” with a hierarchy in which all memory images exist at multiple levels from the most particular to the most general.24 We commonly identify things in our experience as being of certain kinds, and this is the effect of projecting general memory images onto them. Memory images literally merge with pure perceptions, so in such instances we actually do see the object’s particular qualities, but vaguely as our perception passes quickly into action. At the opposite extreme is the recognition of certain individuals in which our particular memory images of them are applied.

Choosing a course of action may entail closer examination of the objects before us. Coming to the fork in a trail, I initially see the two routes, and I pause to compare their different conditions, specifically looking for likely features such as puddles of water, fallen logs and big rocks. I thus bring forth generic memory images of these objects that overlay the pure perceptions of the scene. Progressively detailed memory images can be called up and projected, as I wonder if the small dark object on the rock is a snake or if the motion in the puddle is water rising from a vernal spring. After my study of the scene reaches a satisfactory conclusion I choose to continue my hike on one or the other paths.

Situated in between the coming and going of pure perceptions and memory images is the body. Its attitude determines the virtual actions that produce pure perceptions that, while being overlaid with memory images, send impulses through the body’s sensory-motor system, finally issuing in some physical movement. Studying the scene sets up a circuit in which the virtual action becomes increasingly exact, hence the memory images and ultimately the bodily motion. Such exactitude is reflected in the extremely complex structure of the sensori-motor system that receives the myriad impulses and translates them into potentially infinitely diverse physical actions. This system functions as the body’s switchboard whose level of complexity determines the extent of its freedom of action.25

The first step in achieving such freedom is the ability to freeze the flux of becoming in temporally continuous and definitely extended images. Becoming is not extended but rather extensive, so in our perception it becomes spatialized;26 we seem to see things laid out side-by-side in an homogenous space. Also, the continuous projection of memory images onto pure perceptions produces the appearance of events succeeding each other in an homogenous time. Our experience is therefore like cinematography – a series of still photographs rapidly projected onto a spatially extended screen.27

This manner of perceiving the world plus the great variety of physical motions possible for the body and finally the extent of freedom to choose actions adds up to immense ability of the body to act on and control external objects. In Matter and Memory Bergson treats this in evolutionary terms, casting the human course as progress in freedom. In Creative Evolution he adds further intelligent functions to our repertoire that have given rise to our science and extraordinary technology. He asserts that our ability to temporally and spatially expand and contract images goes far beyond present perceptions and that our deliberation includes calling up not just matching but also associated memories. This function permits us to visualize things that are not present, freeing our intelligence from the conditions of present time.28 Our intelligence is further liberated by language, the words of which are signs,29 as well as ideas which we form by picturing our acts of forming images.30 With language and ideas our intelligence can operate in nearly total independence from material conditions.

Bergson’s account of perception began with a description of an extended material body surrounded by spatially extended images. While they dwell in the past memory images are temporally and spatially unextended, then they expand in these dimensions when they re-enter the present. Because Becoming is extensive rather than extended, portions of it literally expand and contract, displaying a range of degrees from virtually pure extended space to virtually pure unextended spirit. Matter and mind do not however differ only in degree, for consciousness is an original indivisible component of Becoming which is otherwise of a physical nature. Therefore Bergson eventually admits that memory images don’t abide in some separate past or spiritual realm while in the state of maximum reduced extension but are simply inactive.31

Nothing in his universe is ever reduced to zero spatial extension, and I observe that much “thinking” consists in silently talking to oneself, an activity that involves subtle motions of the mouth which for him are nascent speech.32 In normal perception memory images not only regain extension but they also merge with pure perceptions, forming “intuitions” in which, as in the immediate intuition of Becoming one both lives and beholds it, the subject enters into the object. He further says that sense perceptions form the nucleus of experiences in which unmixed intuitions of objects form the fringe,33 suggesting the possibility of directly entering into those objects through acts of sympathy.34 In other passages he describes certain intellectual acts of creation as originating in indivisible intuitions. A philosopher, for example, first has an intuition of an entire philosophy which they subsequently bring into material form in words. They may revisit their intuition as they give it a rational verbal presentation, seeming to separate manifold threads within it.35

In Matter and Memory Bergson treats Becoming as unitary, ever-changing and existentially absolutely creative. Insofar as portions of it do not change over time but repeat their pasts they constitute matter and are therefore deterministic. While the body thus has a material nature it also has a measure of freedom. His succeeding book Creative Evolution first distinguishes organic and inorganic portions of Becoming and identifies the élan vital as the absolutely creative and novelty-producing animating force that runs as so many lines through deterministic inert matter.36 As space is the extreme of extensity, the élan is the extreme of inextensity, and he calls it “supraconsciousness.”37

The élan animates perception which represents its manner of operation. Embodied, it exerts itself against matter in an effort to extend its creativity and increase its freedom, with the effect being the course of evolution. Its impetus divides like a sheaf38 into so many lines in the two main directions of instinct and intelligence,39 and breaking through matter absolutely creates absolutely novel forms of life embodied in that matter. Bergson likens the process to a firework rocket shooting into the sky that then burns out and becomes cinders falling to the earth.40 For after the initial burst, the new life form subsides into inertia, continuing to exist as an organism that functions in an habitual manner.

The élan advances along so many continuously branching lines, creating ever-more diverse, complex and free species but also reaching some dead-ends and sometimes even moving in reverse. Ultimately the universe is indivisible, so novel creation isn’t limited to particular species but extends into their surroundings, thus there is co-evolution both of whole organisms41 and their parts. Bergson offers as an illustration the evolution of the eye whose vision requires the coordination of multiple parts and functions and also represents the progress of a single original component of the élan distributed over diverse lines of evolution.42 He compares the action of the élan to an invisible fist pushing up through metal filings, the evidence of which is only their re-arrangement.43 The élan is the vital principle of organisms that otherwise consist of matter, so as an evolutionary force it is like an entire fireworks display in which new rockets continue to shoot through the cinders falling from old burnt-out ones.44

Instinct is one of the two pathways that it has followed, producing organisms with marvelous abilities in the form of bodily memories. Their mode of consciousness is intuition, which is direct awareness of the natures of external objects with which they are intimately and reciprocally related.45 Bergson notes that there is no absolute division between plants and animals nor even humans and nonhuman animals, with the differences being a matter of degree, and where the lines meet on a continuum.46 Nevertheless human intelligence does constitute the extreme in free action.

By nature humans expand their physical capacity by tool-making,47 and, distinguishing inorganic matter from living bodies, he proceeds to describe such matter as suited for the propensity of human intelligence toward geometry.48 While matter is only extensive and not extended strictly according to its representation by geometry, our intelligence treats it that way and, along with our ability to regard time as a series of instants, has produced our incredible technology. Generally within the evolutionary process the élan pushes against the natural resistance of matter, but human intelligence has succeeded in reshaping the nature of matter to serve its own purposes. Because of the ultimate reciprocity in nature the world now to a considerable extent reflects the character of the human species.

While treating evolution in Matter and Memory Bergson seemed to wish to avoid any hint of teleology, suggesting that the human body and its freedom simply constitute a channel for the creativity of Becoming. The élan vital, in contrast, is very clearly teleological, and the philosopher’s shift also appears in his replacing the word “attitude” with “intention” 49 to express that which determines its particular virtual actions and therefore perception.

The natural world is spatially and temporally continuous and contains myriad natural communities, and one of the marvels of instinctive animal life is insect colonies in which its members are not fully individualized but are organic parts of the whole.50 In his final book The Two Sources of Morality and Religion Bergson extends this model to human communities. The solidarity of primitive communities he says is a matter of instinct in which the group functions as a single organism, continually repeating its habits and its past.51 Such groups sharply distinguish between their own members and outsiders, giving rise to inter-tribal conflict and eventually war.52

Having lived through the Franco-Prussian War and World War I and preparing the book for publication in 1932, war was very much a concern for him. He had, in fact, been recruited by France’s Prime Minister in 1917 to approach President Woodrow Wilson and persuade him to bring the U.S. into the Great War for the defense of France and its allies, a mission which he successfully accomplished. While he had portrayed the élan vital as a force for progress, what he later saw around him was not progress but rather prospects of annihilation. So he turned again to the élan to seek redemption.

Natural human communities, he said, were closed like insect colonies, ever-repeating their pasts, as after they had achieved some measure of intelligence with the evolution of consciousness, the progress of the élan halted in them. In his final book Bergson repeats the characterization of the creative force as supra-conscious and therefore now spiritual.53 Historically it has been manifested in particular spiritual leaders who embody the love of all men and disseminate this love to others54 – figures such as Christ and the Buddha. Societies that assume this spirituality become open and thus channels for the élan to continue its progress.55 For the most part such universal love becomes institutionalized in religious rituals, that is, habits, but Bergson stresses that true spirituality is intensely active with the ceaseless performance of humanitarian acts of love. In this regard he contrasts the more active and outer-oriented Christian faith with more passive and inner-oriented Eastern spiritualities.56

Spirit is embodied in matter, whose nature is inertia, so even with the arrival of enlightenment, humans continue to tend toward the habits of closed societies. Bergson therefore expressed hope for international bodies such as the League of Nations but also remarks that the human population in the early 1930s had grown too large and was a key factor in conflicts.57 He therefore advocated not only population reduction but also a shift away from the global industrial economy to small communities engaged mostly in local food production.58 As this is today’s vision of the ecological civilization,59 Bergson may now be recognized as a prophet for our time, not only for this prescription but also much of his ontology and epistemology. I therefore turn to assess what he got right and where he fell short in offering a system of philosophy which can effectively guide us today.

In the first place, his characterization of time is absolutely correct. It is neither the series of temporally unextended instants assumed by modern science nor an eternal present in which things move about like actors on a stage as Plato and Aristotle assumed. Rather, the universe is Becoming – continually absolutely coming into existence in every present moment and, over that moment of duration or interval, passing away into the past. While Bergson declines to use the word “creation,” I agree with Leibniz’ basic conception of continual creation,60 adding duration to it. For me, Becoming is the continual absolute creation of the universe in every present moment which is not instantaneous but has duration. At every such succeeding moment the universe is created absolutely anew which means not just different from preceding moments but also containing some absolute novelty. Bergson speaks of kaleidoscopic change, but absolute novelty precludes mere rearrangement of previous contents. At every successive present moment its novelty is integrated into the re-creation of the immediate past. Thus as every successive incarnation of the world is new, the past is continually preserved within it, and this is a continuous process in which the past accumulates in the present like a snowball. This is in fact our common understanding of time – every present moment is new, but past experience is always retained in them.

The retention of the past in the present is memory, and Bergson is also absolutely correct in recognizing the re-entry of the past into the present, which is nothing but the activation of memories that are otherwise retained in an inactive state. This is particularly evident in the case of bodily memory, for what is retained isn’t an action such as performing a dance step one has learned, but the ability to reproduce it. Our bodies contain countless bodily memories like this, thus my act of sitting activates my bodily memory of that function while my bodily memory of standing remains inactive.

As he asserts, image memory is different and must be understood in relation to actual present perception. In this last matter Bergson is basically right in locating present sensory images, particularly visual ones, where they really are, which is outside the body. Our visual perception is three-dimensional, and my images are over there, at a distance from my body and approximately in the places of the objects of which they are the images. This is a self-evident fact of experience.

He is also correct in stating that images reflect potential action of my body. The universe is ultimately indivisible and continuous, so the separation of the images of things in our perception is effected by our attention that draws outlines around them, so to speak, indicating where we might touch or grasp them. Likewise with perspective; it indicates how far we must move our bodies to come into contact with objects. Finally the kind of images that we perceive is determined by our nature and interest, for we can’t imagine an ant, for example, seeing the things that we see and in the same way.

Bergson has images being formed by the reflection of our virtual action back from external objects, and to some degree this is correct. In the continuous universe the body is not really separate from its environment, so its influence does extend beyond its body and affects external things. The same is true of the object, so it follows that the influences conjoin in what for him is the image. It also follows that the influence that forms the image to some extent prefigures bodily action determined by a present intention, for we literally observe perceptions passing into actions.

The philosopher’s trouble, in my view, comes with how he deals with memories contained in present perceptions. Our bodies obviously possess the ability to somewhat recreate past perceptions, and to some degree memory images do interpenetrate and overlay present perceptions. Interpenetration is displayed in the very duration of perception in which we observe present images passing into conscious memory images, especially in inattentive perception. Overlaying is evident when we misread or mis-hear words and generally when we seem to see things that aren’t there – the camouflage of an animal for example or a stranger whom we first seem to recognize as an acquaintance. While memories do enter present perception, they don’t do so on anywhere near the scale that Bergson says they do.

For him scientific understanding is derived from the spatialization of duration through the overlaying of pure perceptions with memory images and is therefore artificial. Yet he applies the reductionism of the sub-atomic physics of his time to explain some elements of his system in micro terms. Thus his characterization of the world as composed of images alludes to a world of sub-atomic entities in constant flux, and he defines colors as forms of high-frequency electro-magnetic radiation. The consequence of these assumptions is that pure perceptions are momentary and conscious attention must impart its own content, continuity and duration to them in order to produce the stable images of normal experience. This it does with a flood of memory images re-entering present perception from the past to fairly submerge the actual present content.

Apart from his problem of applying a model that he has dismissed as artificial, this account doesn’t even accurately represent our normal experience. Our lives are carried on at a macro, not micro level, and our relationships with things are mostly at our own scale. As there is continuity between our bodies and our surroundings so our durations are synchronized. Our experience consists of continuous images of continuously existing though changing things that do include memories and reflect our potential action on those things. Especially inattentive experience may give it a somewhat cinematographic quality, but this is not the norm.

The seeds of a more plausible version are contained in Bergson’s own work. Intuition of duration, he says, places us immediately within it as we simultaneously live and observe it by relaxing the tension of our consciousness. Pure perception is also intuition in which we are merged through the image with its object. He even calls common perception “intuition” as it is the condensation of innumerable pure perceptions and activated memory images into our rhythm of duration. What is most revealing, however, is his comment that such sensory perceptions form the nucleus of experiences in which immediate intuitions of external things form a fringe. He suggests the possibility of intuiting these entities directly through acts of “sympathy” which is the normal mode of instinctive consciousness.61

While he casts his epistemology in micro-terms, his ontology treats macro phenomena, for he has the body being a highly organized center of action that obviously interacts with other macro phenomena. It doesn’t search for subatomic entities, but rather food, at the most primitive level, in the form of fruits, fish and game. Creative Evolution reinforces the reality of concrete organized entities up, down and across the great chain of being, and Bergson acknowledges their spatial continuity as this is understood by the science of ecology. He rather sharply distinguishes between organisms and inert matter, but this is ultimately a difference of degree. Present understanding basically affirms the Gaia hypothesis, so Becoming may be regarded as universal life.

Creative Evolution describes organisms which are matter animated by particular strands of the élan vital and are therefore Aristotle’s essences62 updated in light of ecological understanding and reframed to acknowledge the true nature of time revealed to us by the French philosopher. What follows is my synthesis of the thinking of these two philosophers which is driven by the desire to create a new philosophy for our time that serves our current urgent needs. Along with its clearly teleological character, it follows the Greek in maintaining that things can only be explained to the degree that they permit explanation.63 Thus it falls far short of science and Bergson’s scientism, but it includes vital content that science lacks – specifically a satisfactory account of consciousness and practical moral direction.

Expanding Aristotle’s essentialism to accommodate ecology first involves recognizing collective essences to which individual ones belong, and these exist on so many levels – families, communities, habitats, ecosystems and ultimately the biosphere. The individual therefore possesses multiple identities in which it functions in these various capacities. As for Aristotle form is function,64 an individual is functionally extended into objects around it – beyond the boundaries of its body – and this is how sensory images come to be outside the body. For Bergson they are formed by the intersection, so to speak, of the subject’s and object’s virtual action, which in Aristotelian terms means the functional conjunction of the subject qua seeing and the object qua visible or the joint actualization of these two potentialities that forms the image. Unlike the French philosopher’s multi-step process, the latter interaction is immediate – the image simply comes into being, and this is what we observe in our common experience.

Bergson expands the content of images to include in addition to generic visual qualities memories and the subject’s intention which are present in their essence and therefore enter into the image. While Aristotle locates visual images in the eyes,65 he asserts that we intuit the essences of things in a process consisting of the actualization of their forms that potentially exist in the mind.66 The French philosopher also has us intuiting things’ Becoming in the fringe of the nucleus formed by the image. In point of fact we do intuit the Aristotelian essences of things while we perceive their sensory qualities, both approximately in the places of their objects. Our body is surrounded by visual images and intuitions that form a three-dimensional space of consciousness, and this represents our functional conjunction as a conscious subject with external objects as objects of consciousness. This is a simple and irreducible function of our essence.

While Bergson in Creative Evolution has things manifesting the universal animating force within them by striving to create and break free of matter’s determinism, Aristotle accepts the self-evident teleology of organisms which is to carry on their organic functions and perpetuate their lives into the future.67 This they do as individuals and also as organic parts of the multitude of wholes of which they are parts. By nature therefore human animals strive to live well as individuals and as parts of communities, ecosystems and ultimately the biosphere. Indeed they strive for not just adequate individual and collective lives, but perfection in all of them.

Aristotle attributes failure to achieve perfection to material deficiencies in things,68 and these extend to human education. While the will to live exists in Bergson’s organisms it does not include an aim for excellence, and humans furthermore possess general freedom to choose their actions. Over the course of evolution they have advanced in the direction of science and technology for the purpose of controlling nature.

The means of such progress is their intelligence that operates far beyond the function of present perception that offers choices for action, since every sensory experience, according to Bergson, is preserved as a memory image which can be re-activated for the purposes of remembrance and recombination to produce new visualizations. Such images literally expand and contract as they merge with extended external present images or assume a more “mental” or interior character, ultimately becoming entirely un-extended as they pass into unconsciousness or inactivity.

While we actually see images of things spatially expand and contract as we move closer and farther away from their objects, and their passage away into memory extinguishes both their spatial and temporal extension, we have no other direct evidence that images behave as Bergson says. Instead, images come into consciousness already having some extension. We do observe, however, images passing into actions and actions passing into images, which is understandable since we are ultimately an indivisible Becoming with a certain nature.

Thus at every present moment, which has duration, we, as part of the total Becoming universe, are created anew with absolutely novel content being incorporated into the immediately preceding content which continually accumulates like a snowball. Conjoining with external objects to produce images brings one’s entire past to bear on this act which is particularly determined by our intention. Beyond survival and desire for freedom, Bergson has little to say about the intentions embodied in our perceptions. These are in fact myriad and highly specific, therefore I don’t just see different colored shapes that indicate how I might touch and handle things. Rather, my perception embodies my desires to see and act upon specific kinds of things. For example, at the market I want to buy Gala apples, so I pass by the other varieties that all have apple-shapes and colors, resting my eyes on the display of Galas. I further look at each one, searching for bruises on them in order to pick some without blemishes. Doing this reveals that I have a sense of an ideal apple which for Bergson is an idea defined as a picture of my act of forming the image of the apple.

Our experience of things isn’t limited to perceiving their sensory qualities, as I immediately know what things are in intuitions of their essences. For me apples aren’t just round and red objects but rather fruit which I might eat, and this quality or nature of theirs which I am aware of is not visible. Along with sensory memory images, memories of intuitions are preserved in our substance, and we can re-activate them along with image memories. Remembering a person we know, for example, isn’t just like retrieving a photograph of them – their image, rather we recall them – their essence – in the memory of an intuition.

Things have manifold essences, and our intentions are directed at particular natures or identities among the several which they possess. We relate to and literally experience other people in various capacities – family member, fellow citizen of our community, living organism and so on – while specifically acting in corresponding capacities.

That the universe consists of innumerable nested and intersecting lives is the fundamental truth of ecology which Aristotelian essentialism must accommodate. Each human being is essentially an individual and an organic part of all of these larger whole essences and by nature acts to serve them all, indeed with the intention of achieving their perfection. This natural function is subject to corruption by human cultures which are so many habits obstructing our freedom to judge situations and choose courses of action that fulfill our manifold intentions.

Each person has their entire past experience to draw upon in such decisions. As their own past snowballs so does that of the world, providing us with human and natural history as resources. Applying the tools of science to these has given rise to the idea of the ecological civilization, which represents the object of our universal intention that guides free action. Obviously a certain kind of education is required to arrive at this ideal and, most importantly, to furnish awareness of steps to be taken to actualize it.

Holding the ideal while possessing some practical knowledge and past experience shapes one’s present conscious experience, so situations are literally revealed as opportunities to act in pursuit of the goal. Human life is complex, and we presently fall far short of the ecological civilization on every front, which is to say in regard to all of the nested and intersecting wholes of which we form parts. Our culture’s overall conflict with nature involves our social arrangements which are ultimately our greatest resource for making change, as one person can’t do it alone.

Although Aristotle didn’t recognize collective essences, he regarded the family as a natural unit.69 He also famously said, “Man by nature is a political animal,”70 and declared that the philosopher-king was the highest fulfillment of human nature. There has never been a perfect monarch, and history has moved on to democracies in which all the citizens are the sovereign. By nature therefore in a democracy, people’s highest and primary identity is as citizens. It is especially in this capacity that we see that people have fallen gravely into inertia and that mass citizen action is the solution to our current crises.

The universe is a Becoming in which every present moment is brand-new, also incorporating all of the past into itself. Every part participates in the universal Becoming, either in creating the new or preserving the past by persisting in inertia. Individuals’ single actions to advance the ideal generally move the needle a miniscule amount before they ripple away into space and the past. While persistent targeted individual action compounds and has greater impact, substantial change requires significant numbers of people organized to take effective steps towards the goal.

In his final book Bergson identified the élan vital as the single animating force in the universe which in the last stage of which he knew brought forth a spirit of the love of all men. Now in our time the élan has created yet another spirit – that of the love of all living things – and it is spreading among people. Some folks are becoming imbued with it but generally remain unclear as to exactly what they should do, while others are yet untouched but still know that something is terribly wrong with the world.

For Bergson we are immediately aware of creation in acts of intuition, as in the poet’s indivisible intuition of a poem that proceeds to materialize into words and in this form becomes an enduring part of human culture.71 William Faulkner’s famous words “The past is never dead. It’s not even past”72 has been amended by a more recent author with “All of us labor in webs spun long before we were born, webs of heredity and environment, of desire and consequence, of history and eternity.”73 So as history furnishes circumstances it also provides infinite resources that may re-enter the present as memories supporting the actualization of present intentions.

There is a zeitgeist or, more precisely, a series of them over the course of history, and they are embodied in both people and their enduring works that include philosophy. People know that the modern age is about over, but what comes next? We’re definitely at a fork in the road with one way being that of authoritarianism, extreme wealth inequality and environmental, especially climate devastation, with the other being robust democracy, social justice and environmental regeneration. Philosophy serves to present a worldview defining what the world is and people’s role in it and, above all, providing motivation for people to act in a certain way. The worldview that is passing away includes liberal democracy as well as a vision of unending progress in science and technology that delivers ever more material benefits to humanity. With both of these ideals failing, it’s evident that to effectively embody the zeitgeist a new philosophy must work in practice; in fact this is the primary criterion by which it is to be judged.

Therefore I have laid out a system that incorporates the thinking of two classic philosophers that people who believe in the myth of progress are likely to dismiss as outdated at best or wrong at worst. But Becoming renews the past; in fact brings it back to meet the present. I point out that participatory democracy dates back to Aristotle’s Athens, Rousseau’s Geneva and colonial American town halls. Science undoubtedly has benefits but must obviously be controlled. The ancient Greek virtues for which people were said to strive were courage, wisdom, temperance and justice. Practicing them involved determining the “right measure” of the thing in question in the given circumstances. Aristotle called such judgement in common affairs “practical wisdom” and “political wisdom” in public affairs,74 while for Plato the right measure constituted the justice of a matter.75

As the applications of science must therefore be subject to limits so should its cultural dominance, for it is the fundamental philosophy or ideology of the modern age. Although people expect science to explain everything it spectacularly fails in at least two areas, for it has no satisfactory explanation of consciousness, and its sole moral concept is progress. My philosophy doesn’t aspire to explain everything but rather adheres to Aristotle’s view that we can only explain things to the extent that they permit such understanding. Otherwise it excels in defining moral action, supplying a method for identifying productive opportunities and finally, providing the motivation to take effective action.

My synthesis of Bergson and Aristotle has the élan vital coursing through an otherwise material world, animating things that are basically the Greek’s essences in their full ecological nature. This “matter” is previous creations of the élan that have lapsed into mostly repeating their pasts or states of inertia which display material determinism. The French philosopher’s work presents a chain of being crowned in Creative Evolution by humans with their promethean technology and in Two Sources of Religion and Morality by spiritual leaders who disseminate the love of all men. This last product of the élan arose in response to humanity’s historical spread beyond closed tribal communities that brought ever-greater conflict and war. I assert that the élan has now brought us yet another spirit – the drive toward the ecological civilization – and this in response to the present human and environmental polycrisis.

Allowing for minor flaws due to the material in which they inhere, Aristotle’s essences attained in his time the perfection of their form to a significant degree and provided humans with accurate intuitions of them. Now we are living amid the wreckage of nature by technology and of the political order by corruption caused primarily by money in politics. As essences are forms in matter, their functions are subject to breakdown and failure, reaching the point at which their forms become extinct and they pass into matter like living bodies passing into dead ones.

Looking out onto the carnage we remain equipped with our individual pasts along with all of human and natural history. This is the matter with which the élan will clothe itself, so to speak, in its incarnation in our time. Insofar as matter is inertial and therefore deterministic, the élan literally seeks openings, opportunities to pass, as Bergson says, through its meshes to create forms that, though embodied in that matter, constitute progress in the direction of the ecological civilization. Holding that ideal as our intention we embody the élan in its present course to the extent that we act, for it is such purposeful action that upon ceasing no longer creates and advances but marks time with the continual repetition of the past.

We all know that our individual lives are indivisible with the rest of the world, and this can produce a terrifying sense of imprisonment. Some people are obviously better-situated to channel, so to speak, the élan than others, and they must take the lead. Ultimately it must become the active force in all people, so we must continually look for and actualize opportunities to talk to people, give them ways to become engaged and build the movement for the ecological civilization. The need is urgent and the time is now, for although now is the only time that is, we create in every present moment the past, that is, the world that all future humans and nonhumans will inherit forever.

At the end of Creative Evolution Bergson considers if and how we might directly experience the élan vital and humbly concludes that the process of writing his philosophy is that experience.76 In more popular terms Ursula Le Guin wrote, “You cannot buy the revolution. You cannot make the revolution. You can only be the revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.”77 The present incarnation of the élan, which is life itself, is being manifested by a multitude of people being immediately aware of their unity with the environment, cultivating intuitive consciousness, co-creation and interbeing, engaging in regenerative agriculture, technology, economic practices and community building, rewilding bioregions, advancing resilience and degrowth, revitalizing civil society with resistance and generally exercising their agency as free human beings seeking to achieve excellence in their own lives and those of all the nested and intersecting lives of which they are living parts. Philosophy aims to articulate the zeitgeist of the philosopher’s time, to provide a lens through which people can view the world and a focal point for diverse energies as well as to verify Victor Hugo’s conviction popularly rendered as “More powerful than all the armies in the world is an idea whose time has come.”78

Notes

- William Butler Yeats, “The Gyres,” In Last Poems and Two Plays (Dublin: Cuala Press, 1939), 5.

- Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory, trans.N.M. Paul and W.S. Palmer, (London: George Allen & Co., LTD, 1913), 239.

- Henri Bergson, An Introduction to Metaphysics, trans.T.E. Hulme, (London: MacMillan and Co., Limited. 1913), 8-11.

- Bergson, Matter and Memory, 265.

- Ibid., 297.

- Ibid., 29.

- Ibid., 23.

- Ibid., 269.

- Ibid., 5.

- Ibid., 6-7.

- Ibid., 1.

- Ibid., 30.

- Ibid., 30.

- Ibid., 79.

- Ibid., 19.

- Ibid., 197.

- Ibid., 93.

- Ibid., 26.

- Ibid., 68.

- Ibid., 80.

- Ibid., 313.

- Ibid., 80.

- Ibid., 178.

- Ibid., 222.

- Ibid. 57.

- Ibid. 125.

- Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution, trans. Arthur Mitchell, (London: MacMillan and Co., Limited, 1911), 322.

- Ibid., 190.

- Ibid., 166.

- Ibid., 167-8.

- Bergson, Matter and Memory, 181.

- Ibid., 168.

- Bergson, Creative Evolution, 52.

- Ibid., 186.

- Ibid., 251.

- Ibid., 263.

- Ibid., 275.

- Ibid., 104.

- Ibid., 141.

- Ibid., 264.

- Ibid., 154.

- Ibid., 101.

- Ibid., 100.

- Ibid., 262.

- Ibid., 187.

- Ibid., 13.

- Ibid., 146.

- Ibid., 48.

- Ibid., 47.

- Ibid. 175.

- Henri Bergson, The Two Sources of Morality and Religion, trans. R. Ashley Audra and Cloudesley Brereton with the assistance of W. Horsfall Carter, (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1935), 1.

- Ibid., 255.

- Ibid., 202.

- Ibid., 69.

- Ibid. 257.

- Ibid., 215-16.

- Ibid. 278.

- Ibid., 296.

- Jeremy Lent, “What Does an Ecological Civilization Look Like?”, Yes! (Spring, 2021), https://www.yesmagazine.org/issue/ecological-civilization/2021/02/16/what-does-ecological-civilization-look-like.

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Theodicy,§31.

- Bergson, Creative Evolution, 186.

- Aristotle, Metaphysics, VII.6,1031b18.

- Aristotle, Posterior Analytics, I.3.

- Aristotle, Physics, II.3, 195b23.

- Aristotle DeAnima, II.7.

- Ibid., III.4.

- Aristotle, Physics, II 2, 194a27.

- Ibid., I.9

- Aristotle Politics, I.2.

- Ibid., I.2, 1253a1-3.

- Bergson, Creative Evolution, 111.

- William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun, (London: Chatto & Windus, 1919), 85.

- Greg Iles, The Quiet Game, (London: Hodder & Stoughten, 1999), 210.

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, VI.8.

- Plato, The Republic, IV.

- Bergson, Creative Evolution, 391.

- Ursula LeGuin, The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia, (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), 301.

- Victor Hugo, The History of a Crime: The Testimony of an Eye-Witness, trans. T. H. Joyce and Arthur Locker, (New York: George Routledge & Sons, 1877), 413.